Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Beginner

Lesson Overview:

• Let blues vocalists inspire your phrasing.

• Get more mileage from your licks by varying their rhythmic patterns.

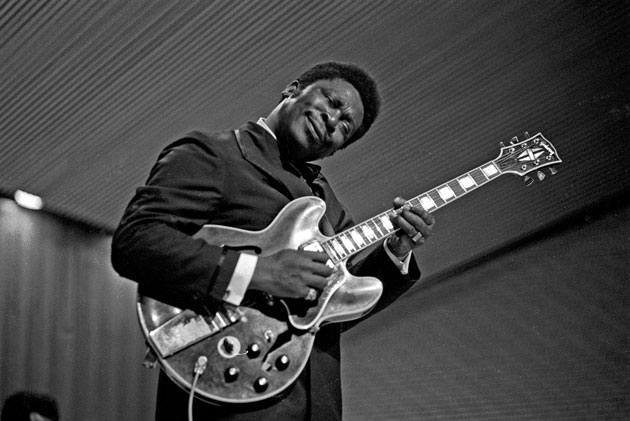

• Emulate the call-and-response style of such blues masters as B.B. King, Freddie King, and Magic Sam.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson’s notation.

“Phrasing” is a term that gets thrown around a lot when people talk about improvisation, and I remember being baffled by this as a kid learning to play. Especially when some rocker would sound off about how awesome his phrasing was in a Guitar Player interview and the next month all the jazz cats would write in to laud the phrasing of their favorite bebopper while unflatteringly comparing said rocker’s phrasing to the flatulence of various barnyard denizens. “Wow,” I would think, “this phrasing thing is clearly a big deal,” while remaining pretty oblivious of what the word really meant.

It turns out phrasing is basically just how you play the things you play. At its most fundamental, it’s where your ideas or licks start and stop within the rhythmic and harmonic pulse of the music. Getting into more detail, it’s your attack and tone and dynamics and personal timing—all the essential details that make you sound like yourself. But for the purpose of this lesson, we’ll stick with the first part: Phrasing is where you put the notes, relative to the chord progression going by.

Specifically, we’re going to explore how modeling the shape, length, and resolution of your ideas on the form of classic blues lyrics can serve as a shortcut to great phrasing over a 12-bar blues. Contouring your playing to the lyric structure of the blues almost automatically results in space, call-and-response sounds, and ideas that draw the listener through each subsequent turning point in the form.

To begin, think about the melody to a classic like “Sweet Home Chicago.” It has a short opening phrase, followed by a longer answer: “da-DAH … DAH-da-DAH-da DAH, DAH-da.” You can hear similar phrasing on blues standards like “Everyday I Have the Blues” and “I’m Tore Down.”

Ex. 1 is the guitar equivalent: a short phrase (just two notes!) that lands on the downbeat of measure one, beat 1, answered by a longer phrase that starts at the beginning of measure two and ends on the and of 4, right on the doorstep of measure three. Notice how the next couple of measures are left empty—the same way the lyrics leave some breathing room (both literally and metaphorically) in “Sweet Home Chicago.”

The second line of many blues lyrics is a repeat of the first line, although, because it is a repeat, singers often work some kind of variation into the melody. You can do this too, by starting your phrases a little earlier or a little later. Just make sure they still resolve in the same place rhythmically, as in Ex. 2.

The third line is generally where both the lyrics and their melody have the biggest change-up, and “Sweet Home Chicago” is a perfect example of this shift. In Ex. 3, the guitar equivalent opens with a short pickup into the downbeat, just like lines 1 and 2, but with new melodic material, and a phrase that doesn’t resolve until beat 3 of measure nine. The answer, which takes you from IV back to I, can be similar to the answers in lines 2 and 3, or a place to insert something new and different.

Cool, so there’s the lyric form—six phrases that take you through a 12-bar blues with the same overall shape and balance as a blues lyric. Now let’s look at a few ways we can build on this framework.

For starters, we can loosen up the phrasing a little. For example, instead of resolving your licks on the first beat of a measure, typically by finishing your phrase on the root, you can delay that resolution a little further into the measure, as in measure one of Ex. 4, or land on the root and keep playing, as in measure three.

We can also draw out the pickup that launches each line, using phrases that start on, say, the and of 1 rather than the and of 3 or 4. Ex. 5 makes the first and second phrases a little more symmetrical, and less like “Sweet Home Chicago,” but still retains the call-and-response feel.

If you do stick to the short-long phrases of the lyrics, there’s a handful of space between your first and second phrase, and a lot of space at the end of each line. Space is great, space is tasteful—and you don’t want to pack all the space full of stuff—but such spaces afford you the opportunity to play your own rhythm guitar hits, which, like space, will contrast nicely with your lead lines (Ex. 6).

If we’re still thinking about this as a vocal approach, we could also use the space at the end of the line for what we all know it’s really best for: guitar fills! Play your call-and-response “vocal lines” in the first couple of measures, then play fills—short licks that respond to all of that—towards the end of each line (Ex. 7).

We’ve been using somewhat consistent licks for lines 1 and 2 throughout the longer examples to keep the focus on how we’re varying things rhythmically, but changing up your licks more from line to line will create further variety, even as the rhythmic shape of the lyric form continues to lend your soloing a satisfying sense of direction and structure. Check out Ex. 8 and see if you can still hear the call-and-response phrasing, the resolution of each phrase, and the overall lyric shape of things, despite incorporating all the various changes we’ve discussed so far.

One more thing, as far as playing over the first line. On the second verse of Freddie King’s “I’m Tore Down,” you can hear the lyrics double up in the first line. It happens over stop-time in the rhythm section, but it works even if the band keeps playing as usual.

As applied to soloing, you can think of it as squeezing a sort of ABAC structure into the first four measures of the form: a short lick in measure one, an answer in measure two, a repeat of the original lick in measure three, and an answer to all of that in measure four, in a way that carries on and resolves to the IV chord at the start of measure five.

For a similar instrumental take on this idea, check out the ensemble riff that leads into Duane Allman’s solo on the Allman Brothers Band version of “Done Somebody Wrong” from the Fillmore recordings.

[embedded content]

Ex. 9 illustrates one way to apply this idea to the kind of licks we’ve been playing. Once you’ve grasped the concept, try dropping it into the first four measures of one of the longer solos above.

Working with the lyric form is not only a great way to develop your phrasing and breathe some space into your solos, it’s a way to go beyond generic jamming to create solos with a real musical connection to the songs you’re playing on. So before you start wailing, take a moment to listen to the words, and you’ll be overflowing with ideas in no time.